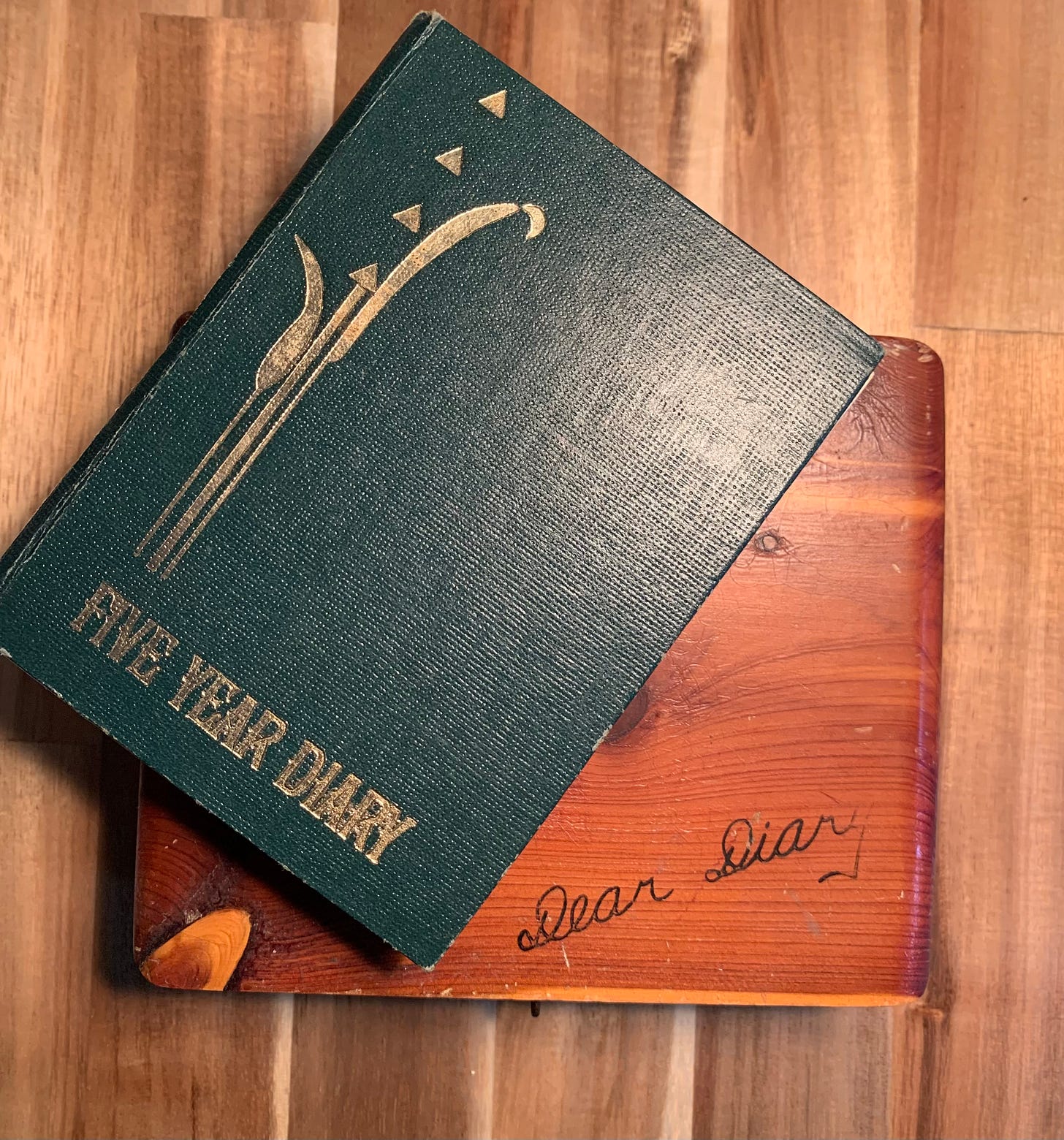

When I was seven years old, I invented a friend. Her name was Godi—I didn’t know the meaning of “gaudy” back then—and she was inspired by this picture:

Godi was born when I opened the door to a family of Seventh-day Adventists. I don’t know how long they kept me there, telling me about God, but eventually they gave me a little booklet and went away. In my room, I tore out this picture and stashed it between the pages of the diary. Everything I needed to build a friend was in that skyward gaze.

I obviously thought Jesus was God (is he? I’m still confused about that) because Godi was the girl version of this beautiful Jesus, without the facial hair. I talked to her in my head and, when I was alone, I talked out loud to her and waited while she answered. Godi was strong and practical. She always reassured me, and she had beautiful eyes.

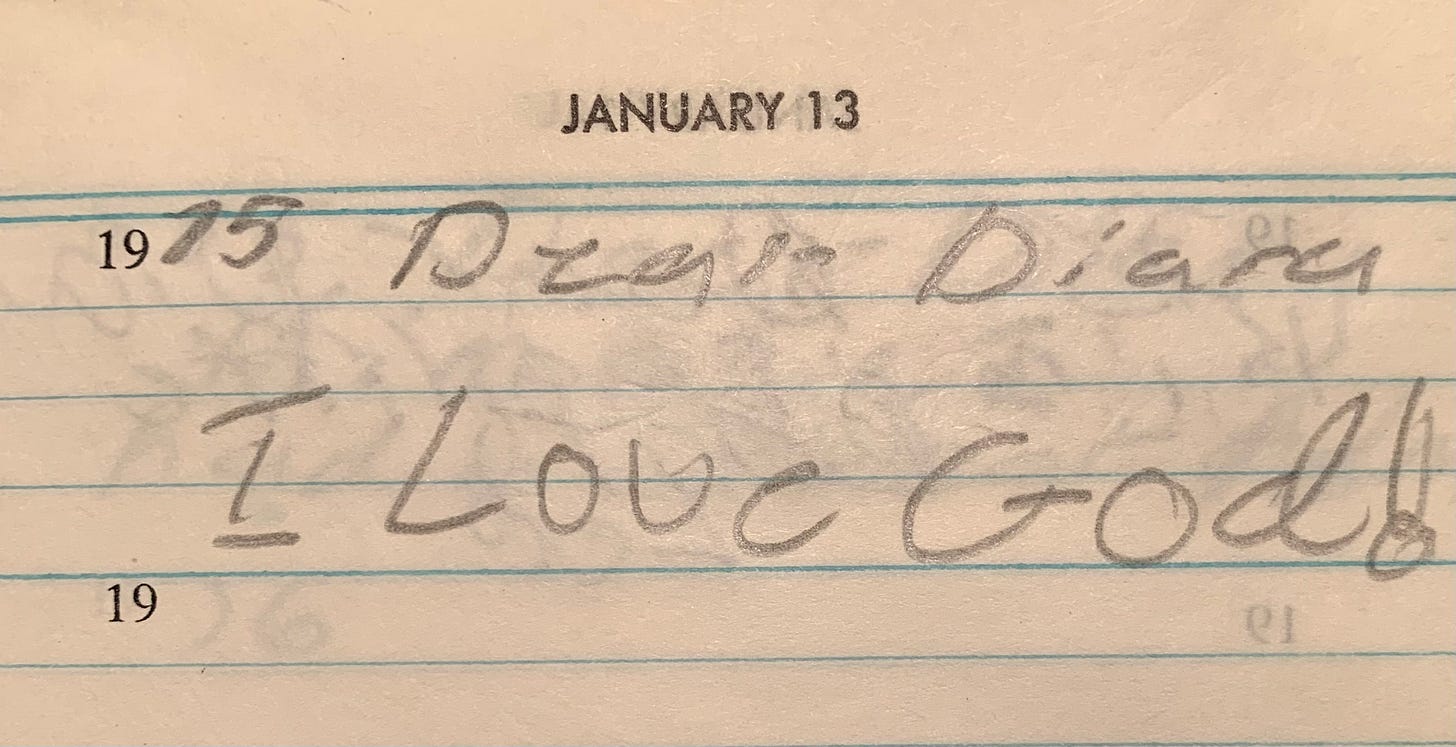

Godi emerged out of a real spiritual crisis. My parents, outspoken in their disdain for organized religion, were not the people I could ask about God. When they weren’t laughing, they were fighting. Dad drank too much. Mom was tired and impatient, and my sister was eighteen, working, and going to the “snow caps” (according to my first entry on January 1, 1975).

Throughout the diary, I agonized about my relationship with God:

It was a guilt-ridden relationship, and because the Seventh-day Adventists told me that God saw everything, even the not-nice things I wrote in my diary, I’d follow up with proclamations for his eyes, like this:

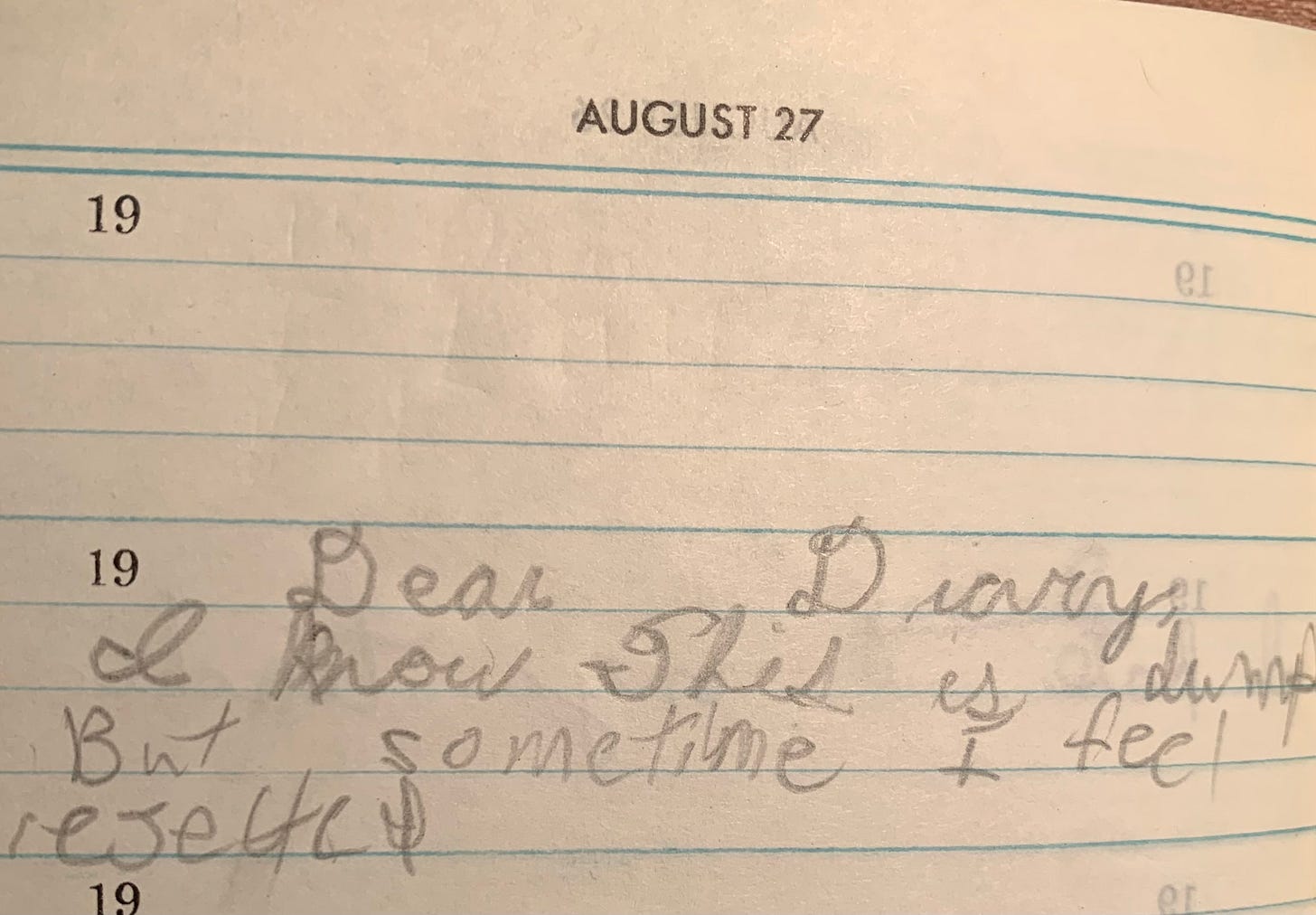

My imaginary friend Godi wasn’t like the Seventh-day Adventists’ God. She’d listen and advise. She never judged, blamed, or rejected me.

Then my parents separated.

We moved from our rented house to an apartment complex, where Mom, my sister and I lived in the family section and Dad lived a short roller-skate away in the adult section. The apartment complex bordered my elementary school. After school, I’d let myself in with the key around my neck.

Alone, I’d talk to Godi and my dolls, or I’d roller-skate over to the adult section and watch Dad drink straight from a bottle of whiskey.

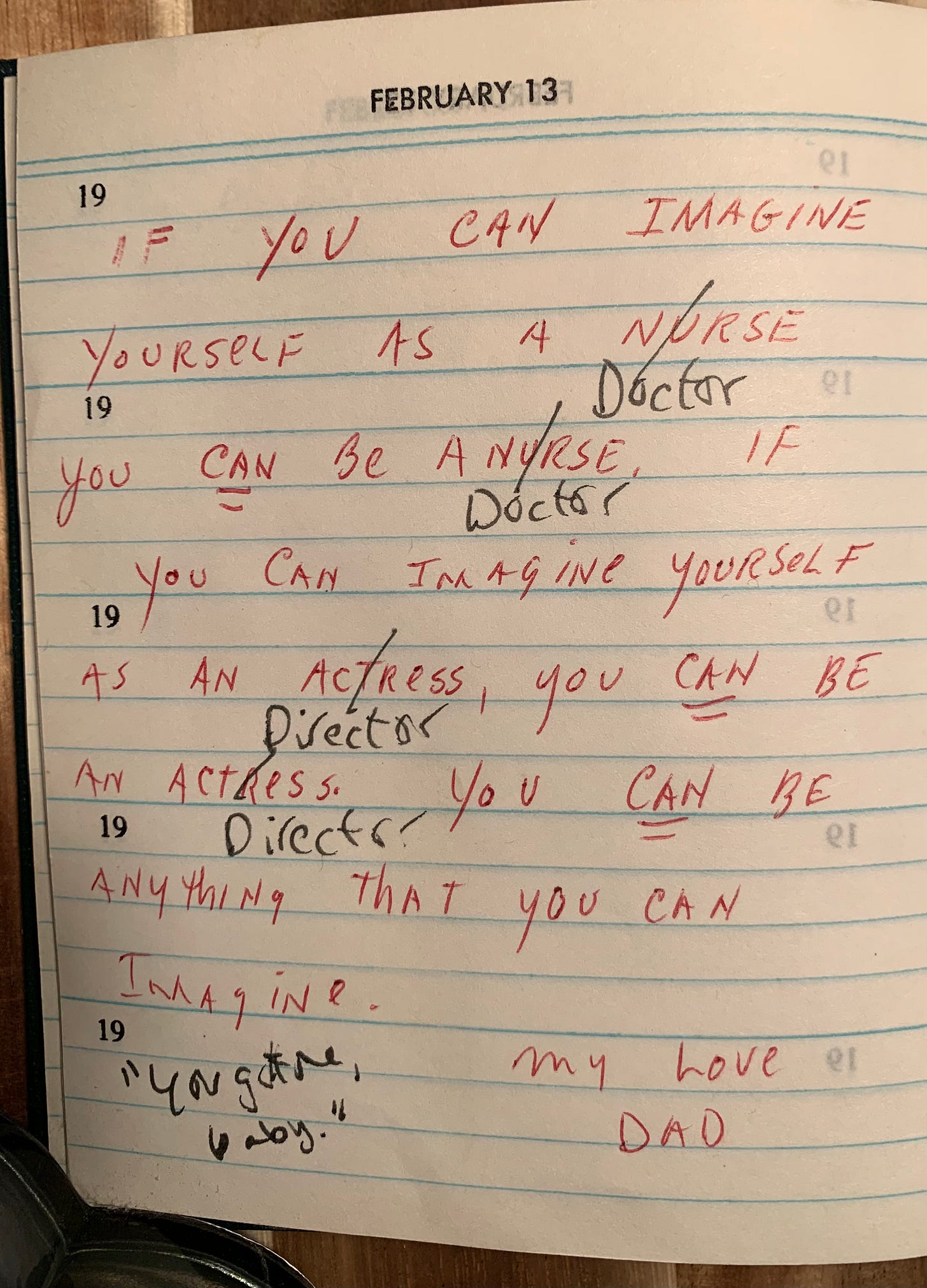

The separation didn’t last. Soon, we were all together again in a new rented house. Dad got bowel cancer, survived, and drank less. Mom was upbeat more often. My sister left home to start her own life. Later, when I came home from studying at UC Berkeley, I revisited my first diary and found this:

If Berkeley taught me one thing, it was that this shit couldn’t go unchallenged. I made the corrections and showed Dad. He shook his head and said, “you got me, baby” which I wrote on the page. Then I slipped the picture of Jesus back between the leaves and wondered when I lost Godi.

Leila it must be amazing to read these diary entries as a mature person. I was heartbroken by your vulnerability as you dealt with changes in your family situation by inventing Godi—I just wanted to hug you. And I loved how, after coming home from Berkeley, you saw things more clearly. ‘If Berkeley taught me one thing, it was that this shit couldn’t go unchallenged!‘ And you know, I loved your father's ambition for you, because even though it was limited by his experience and outdated attitudes, it came out of his love. Thank you for sharing that.

Shelley

I can't love this enough.